Because the land must be defended / Or there will not be place for the revolution.

-Internationalist Commune of Rojava

Despite the threat of Syrian war crimes, Turkish ethnic cleansing, and the militant fanaticism of the Islamic State, the autonomous polyethnic community of Rojava makes environmentalism—alongside women’s liberation and direct democracy—central to its revolution in Northeast Syria. Such commitment starkly contrasts the slow, piecemeal, and shortsighted actions that define the United States’ response to the climate crisis. Our politics discusses environmental action as an afterthought and implements it within existing political and economic systems that strip it of urgency and effectiveness. Because of this, the calamitous predictions of UN climate reports are matched only by the deafening silence of the US and other wealthy nations that fail to implement structural change. Given this precedent, Rojava is revolutionary. Not just in its actions, but in its mere existence as a community trying to put the planet first.

Source: Flickr / Kurdishstruggle

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, more often called “Rojava,” broke away from the Syrian regime in 2012 to form a self-governing collective. The administration pursues a 3-pillared model of “democratic confederalism” intended to counteract oppression in every aspect of society, including that of the planet (Hammy & Miley, 2022). Patriarchy, viewed as the oldest and most fundamental form of oppression, is fought (often literally) with legal/economic opportunities outside of traditional gender roles. Direct democracy runs through local councils, granting communities control over their own economics, agriculture, and criminal justice. Environmentalism in Rojava is emphasized as both a scientific and social necessity. Intense droughts and import embargoes alike make climate resilience and sustainable resource-use essential, while Rojava’s commitment to “social ecology” theory—that ecological crises stem from fundamental social problems—centers environmental action in the administration’s pursuit of a just revolution (Internationalist Commune of Rojava [hereafter “ICR”], 2020a).

Source: Rojava Information Center

Though Rojava holds environmentalism as a core principle, the barriers to realizing this principle go far beyond congressional gridlock or American consumerism. War remains an ever-present reality in North and East Syria: Assad’s Syrian regime crushes dissent in its former breadbasket with chemical weapons, ISIS considered the secular polyethnic community to be heretics deserving slaughter, and Turkey still sees the administration as a Kurdish terror group writ large. Thus, practical realities hamstring Rojava’s green aspirations. The nearby Tabqa dam could supply electricity for the entire region if not for ISIS sabotage, Turkish shelling, and an import embargo on replacement parts rendering four of its eight turbines inoperable. Turkey leverages its upstream control of the Euphrates River and surrounding infrastructure to restrict water flow and further reduce the dam’s output (Broomfield 2021). To mitigate the lack of hydroelectric capacity, the region must rely on “mazut,” crude diesel fuel from local oil deposits. But, historically deprived of non-extractive infrastructure by the Syrian regime, Rojava cannot refine its own crude oil, giving them the choice of two damning options: Export crude to regime-controlled refineries, or use wildly dangerous homemade refineries prone to contaminating groundwater and exposing residents to a litany of carcinogenic toxins (Zwijnenburg, 2020). Yet despite these ecological and ideological setbacks, the collective still works to keep its green dream alive.

Even as wartime pressures force a reliance on diesel fuel, the administration has revitalized its territory and planned for long-term sustainable infrastructure while the US continues to drag its feet. Agriculture in Rojava is planned by its farmers, whose local cooperatives rotate diversified crops to meet each region’s specific needs (Rojava Information Center, 2020). Experts from the project’s agricultural committee work with cooperatives to choose what to grow, avoiding soil-depleting monocultures with the ultimate goal of rejuvenating topsoil and eliminating chemical fertilizers (ICR, 2020c). The “Make Rojava Green Again” project coordinates sustainability efforts across the region, from cultivating tree nurseries in deforested areas to constructing riparian buffers and wastewater recycling facilities to counter water scarcity (ICR, 2013, 2019, 2020b). Even emissions regulations for fossil fuels are controlled by those immediately affected, elegantly subverting the familiar “NIMBY” ethos to encourage aggressive environmental protections (Ferretti, 2017). Action from local democratic councils has shut down crude refineries in favor of “semi-professional” refineries with significantly lower emissions and health hazards (Zwijnenburg, 2020).

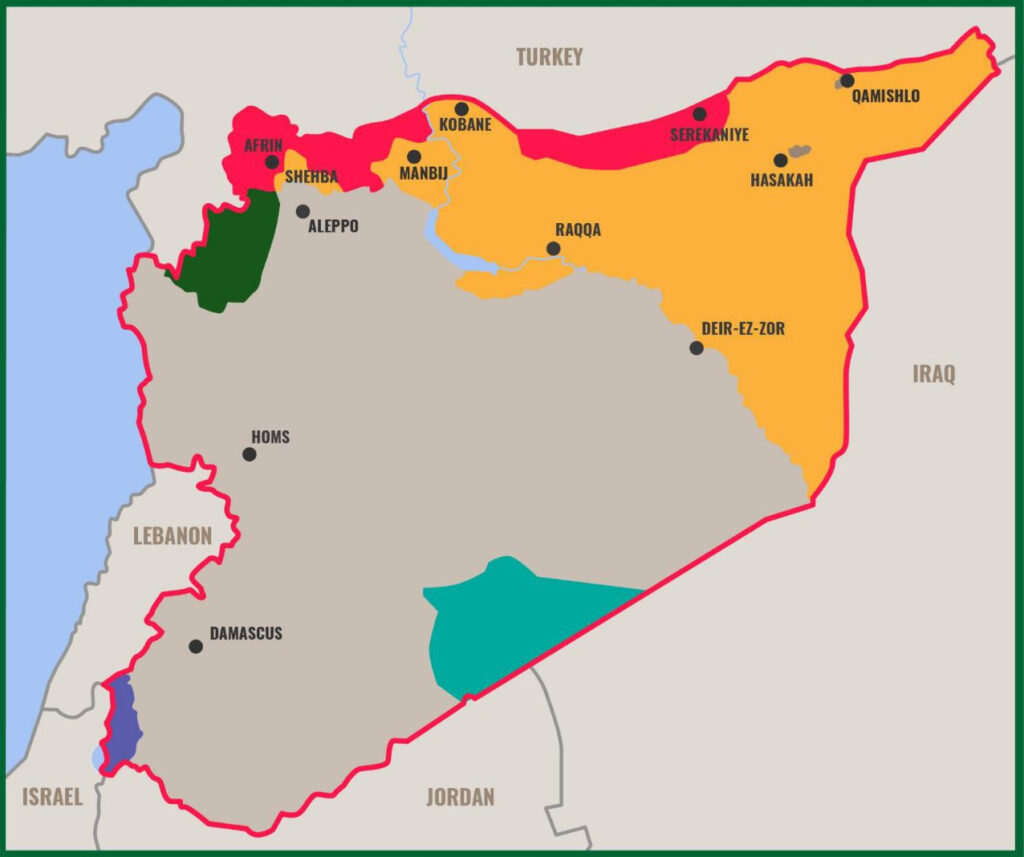

Though Rojava’s sustainability efforts are hampered by constant war, they are immensely more progressive than those of their neighbors. Before the region’s independence, the Syrian regime extracted oil and agricultural wealth through quasi-colonial policy wielded as a weapon of ethnic cleansing against Kurds, ensuring their dependence on the state through enforced deforestation and soil depletion (Broomfield, 2018). Olive and wheat monocultures turned swaths of the Fertile Crescent into “endless, empty fields” (Loo, 2016). Since the 1970s, Turkish overuse has almost halved the downstream flow of the Euphrates River (Hammy & Miley, 2022). And this history is repeating itself. Following Turkey’s 2018 invasion of Afrin (see map), Turkish-backed militias “pillaged” olive farmers to finance further their operations (Kajjo & Sahinkaya, 2020; Petti, 2020). Looting and extortion by Turkish militias have become flashpoints for human trafficking, ethnic cleansing, and torture of Afrin’s Kurds (United Nations, 2020). With this history, planting trees, vegetable gardens, and water conservation are themselves revolutionary acts.

Why, after the failure of COP 26 and “Build Back Better” languishing in the senate, do I bring up Rojava? It is a reminder that—contrary to America’s hegemonic deference to “free” markets, a society can make structural changes to function with the environment in mind. I will not demand that the US adopt Kurdish radical anarchism, these situations are wildly different. But our country must center structural environmental action in our politics. Despite war, persecution, and the difficulties of building an administration from scratch, Rojava is enacting structural change to mitigate the looming climate catastrophe. What on earth is our excuse?

References

Ahmed, K. (2020, April 24). Makeshift oil refineries a necessary evil for locals in north-west Syria. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/24/makeshift-oil-refineries-a-necessary-evil-for-locals-in-north-east-syria-study-finds

Broomfield, M. (2018, February 18). Planting trees below Turkish bombs in Syria. New Statesman. https://www.newstatesman.com/uncategorized/2018/02/planting-trees-below-turkish-bombs-syria

Broomfield, M. (2021, February 15). Rojava is Trying to Build a Green Society, But Turkey is Starving It of Water and Power. Novara Media. https://novaramedia.com/2021/02/15/rojava-is-trying-to-build-a-green-society-but-turkey-is-starving-it-of-water-and-power/

Ferretti, F. (2017, January 18). Revolution In Rojava By Michael Knapp, Anja Flach, And Ercan Ayboga. Society and Space. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/revolution-in-rojava-by-michael-knapp-anja-flach-and-ercan-ayboga

Hammy, C., & Miley, T. J. (2022). Lessons From Rojava for the Paradigm of Social Ecology. Frontiers in Political Science, 3. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpos.2021.815338

Internationalist Commune of Rojava. (2013, November 13). Reforestation in Hayaka. Make Rojava Green Again. https://makerojavagreenagain.org/project/reforestation/

Internationalist Commune of Rojava. (2019, August 27). Internationalist Commune tree nursery. Make Rojava Green Again. https://makerojavagreenagain.org/project/tree-cooperative/

Internationalist Commune of Rojava. (2020a). Homepage. Make Rojava Green Again. https://makerojavagreenagain.org/

Internationalist Commune of Rojava. (2020b, May 1). Stream Buffer. Make Rojava Green Again. https://makerojavagreenagain.org/project/stream-buffer/

Internationalist Commune of Rojava. (2020c, November 21). Agriculture in a revolution. Make Rojava Green Again. https://makerojavagreenagain.org/2020/11/21/agriculture-in-a-revolution/

Kajjo, S., & Sahinkaya, E. (2020, December 16). Syrian Kurdish Farmers Accuse Turkey-Backed Militias of Seizing, Taxing Olive Crops. VOA. https://www.voanews.com/a/extremism-watch_syrian-kurdish-farmers-accuse-turkey-backed-militias-seizing-taxing-olive-crops/6199577.html

Loo, P. (2016, December). ‘A real revolution is a mass of contradictions’: Interview with a Rojava Volunteer [Transcript]. Novara Media. https://novaramedia.com/2017/02/01/a-real-revolution-is-a-mass-of-contradictions-interview-with-a-rojava-volunteer/

Petti, M. (2020, November 23). The Olive Oil in Your Local Store May Be Funding Syrian Warlords. The Daily Beast. https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-olive-oil-in-your-local-store-may-be-funding-syrian-warlords

Rojava Information Center. (2020, November 8). Cooperatives in North and East Syria—Developing a new economy. https://rojavainformationcenter.com/2020/11/explainer-cooperatives-in-north-and-east-syria-developing-a-new-economy/

United Nations. (2020, September 15). Syria: Bombshell report reveals ‘no clean hands’ as horrific rights violations continue. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/09/1072402Zwijnenburg, W. (2020, April 24). Dying To Keep Warm: Oil Trade And Makeshift Refining In North-West Syria. Bellingcat. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/2020/04/24/dying-to-keep-warm-oil-trade-and-makeshift-refining-in-north-west-syria/